Your Data is Yours

Your data and your lab notebook are your most precious possession. But do you know exactly where all your data is? Can you access it and read it at any time, from anywhere? Findings has very clear answers to those very basic questions.

When working in science, data is your most precious possession. Data is what you produce, data is what you publish, data is what makes science go forward. And the guardian of your data is your lab notebook. When we designed Findings, we made sure you had complete control of your data. But whether you use Findings or not, there are a number of basic questions about your data that you want to make sure you can answer clearly.

Where is my data?

That first question is very simple, yet the answer can be very complex depending on your setup. Is your data spread out in multiple binders, or multiple paper notebooks? Or is it in the cloud, on a server somewhere, on somebody else’s computer? How long would it take to get your data so you can take it with you? All of it? Can you access your data if the network is down, or if you are home? What if you lose your password to a server, stop paying for access, move to a new lab, or the service provider runs out of money and closes down?

With Findings, the answer is incredibly simple. Your lab notebook and accompanying data is right here on your computer. It is always with you, all in one place, for as long as you need it. There is nothing special or hidden about it.

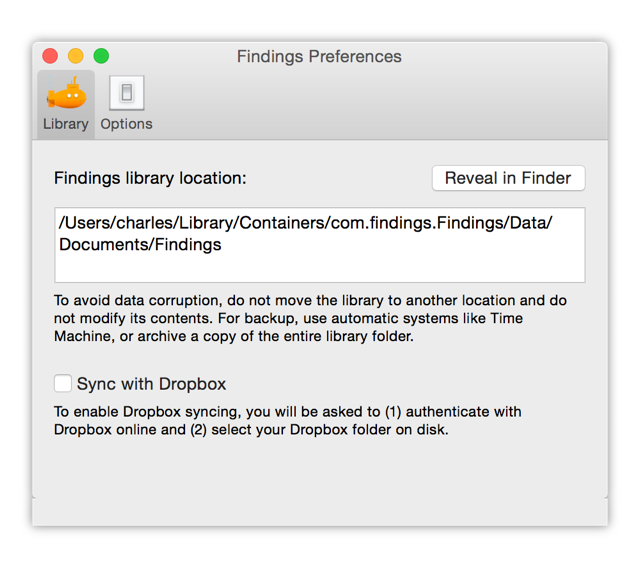

In fact, we want you to know everything about it. Here is how to get to your Findings “core library” on the Mac:

- In Findings, choose the menu Findings, then the Preferences item

- Choose the ‘Library’ tab

- Press the button ‘Reveal in Finder’

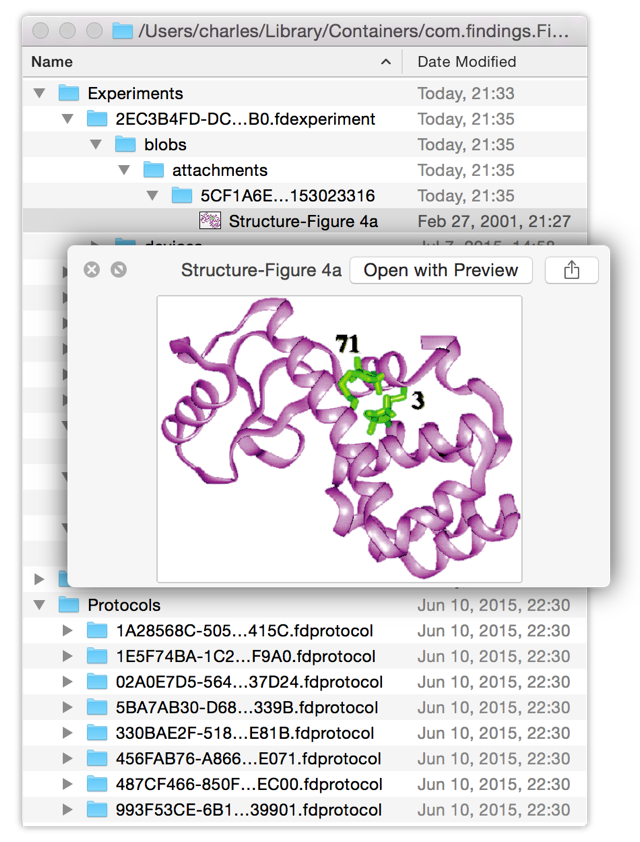

This will select a folder called ‘Findings’ in the Finder, at the path shown in the preferences. This is Findings core library. It has 3 subfolders:

The ‘Local’ directory is the most important. It contains your actual documents, which are organized in sudirectories ‘Experiments’ and ‘Protocols’. Each experiment or protocol is itself a folder that contains your data, using the open-source file format “PARStore” (more on this below). It includes all the attachments in plain sight (any PDF, spreadsheet, image, etc. that you have inserted). If you want, you can open and edit those files using the Finder, but really, it’s much easier to do it from the Findings app (and do not move or rename them).

The ‘PersistentInfo’ directory contains some non-critical, basic metadata about your library, in particular the unique identifier for your device. This identifier is different for each of your Macs or iOS devices. It is random and unique, for instance ‘FD98F23C-43A8-43D1-80AA-70FF67C29B8E’.

The ‘DerivedInfo’ directory contains non-critical derived information about your library, that is used to display your experiments and protocols, and search them. If you delete that folder, it will be rebuilt in a few minutes the next time you start Findings.

Of the three folders, it should be clear that all you really need to pay attention to is the first, which contains your actual data: experiments and protocols. The layout and naming of the files was optimized to provide fast and reliable access for the Finding app, which is why it is somewhat intimidating and mysterious. We plan to make it even easier in the future to browse your data without Findings, but rest assured it is all there, safe and under your control.

What about Dropbox?

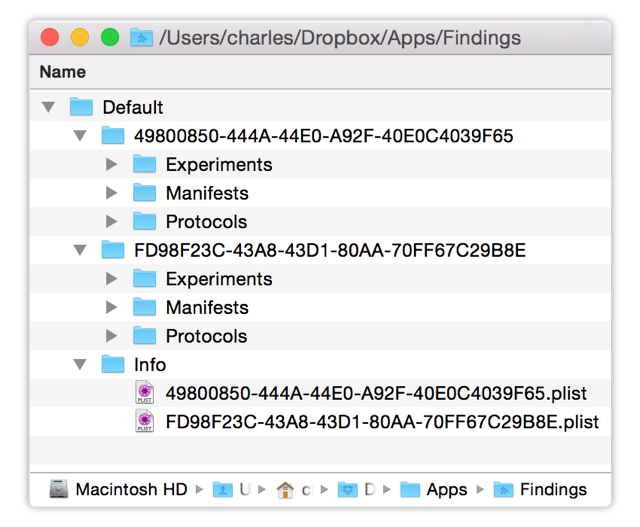

Of course, if you use Dropbox sync, your actual experiments and protocols will be stored on Dropbox. After you enable sync, you will find that the content of the ‘Local’ directory is now empty, and your documents are in your Dropbox folder:

- In Finder, navigate to your Dropbox folder

- Locate the ‘Apps’ or ‘Applications’ subfolder in there

- Locate the ‘Findings’ folder in Apps

You may have noticed that I did not quite explain everything yet about the layout of your experiments and folders in the previous section. But it should now make much more sense in the context of sync, when having multiple devices accessing that same folder via Dropbox (Macs, iPhones, iPads, etc.):

- In the root ‘Default’ folder, there is one folder per device. The folder is simply named after the device identifier (remember it’s unique for each device, as set in the ‘PersistentInfo’ for each of them). The more devices you sync to, the more folders there will be in there. When you create a new experiment on a device, it will be created in the corresponding folder, under ‘Experiments’. For example, if the device identifier is ‘FD98F23C’, it will create new experiments inside ‘FD98F23C/Experiments’.

- Within the ‘Default’ folder, there is also an ‘Info’ subfolder. This is where each device saves a “plist” file, which contains basic information that other devices can read (device name, type, OS version, etc.). I don’t recommend it, but you could delete any of these files, and Findings will create them again next time you start the app from the corresponding device.

- Next to ‘Experiments’ and ‘Protocols’, you will also find a ‘Manifests’ folder for each device. It simply contains a database that keep track of the last changes in your documents. This is used to broadcast its current global status to the other devices, and provide fast and efficient syncing. Like with the ‘Info.plist’ files, you could delete any of these, and Findings will build them again.

Now, you know where all your data is when using Findings, and you know how it is laid out, and what is in there. Whatever solution you use for your lab notebook, make sure you have a good understanding of your data location and organization, and that you can get to it easily now and at any time in the future.

Can I read my data?

Being able to access your data is just the first step. Next, you need to make sure you can read and preserve your data. In a previous post, I explained why you need a lab notebook. Keeping a lab notebook and the accompanying data in good shape has benefits on many different time scales, not just for the subsequent days but also for years to come.

Can you read your data right now? In 1 year? In 10 years? Can you read it if you don’t have access to the original software that created it? Is there any DRM to work around or some other cryptographic system “protecting” the files? Can you easily export it to other formats? Can you create lossless backups of your data? These are not just hypothetical questions. There are too many situations where software locks you out of your own data once you do not own a license anymore; or worse, once it is not developed anymore.

Again, in the case of Findings, the answers are crystal clear. Your data can be read at any time and will remain readable in the future, whether or not you run Findings, whether or not you have a license, and whether or not Findings as a company still exists.

The most comfortable situation is of course to look at your data using the Findings app itself. Even in the worst-case scenarios, you are well-covered. Even if you lose your license (or never had one), even if we stop updating Findings, the current version of the app will always be able to read your files and display their content, forever. You will always be able to export them as PDF, with all the attachments neatly organized for you. The only caveat is that potentially, at some point in the future, a new version of OS X will “break” Findings. Based on past history, this might happen in 5 to 10 years. Of course, you would still be able to run Findings on an older version of OS X, but eventually, you might not even have a computer old enough to do so.

But fear not! Even if you do not have the Findings app itself, or if you do not have a computer old enough to run it in a hypothetical future, you will still have some options and it will not be the end of your data. The experiments and protocols are stored in an open-source format called PARStore. Importantly, this is not just an obscure file format created from scratch using an unknown technology: it really is a simple SQLite database, which is the most ubiquitous file format that ever existed (except maybe for text files), and which is natively supported on billions of devices worldwide. SQLite is used to store the text content of your documents. Then, as mentioned before, the attachments are simply stored as-is inside the file package corresponding to the experiment or protocol, inside a subdirectory ‘attachments’. Of course, you will also want to make sure the attachments will also be readable in the future. For this, it is best to use standard formats like png or jpeg for images, and PDF for graphics or text (we plan to even help you with that part in future versions of Findings).

And that’s not all: there are more options! Findings has support for PDF export, which provides a very simple way to guarantee a permanent record, no matter what. PDF export works even if you do not have a Pro license. We plan to add more export options as well in the future. We really really want to make sure users don’t feel ‘trapped’ in Findings, and want to make sure the way out is always clear if it is ever needed.

Backups

Finally, a post about data would not be complete without mentioning backups. As you probably know, having a backup system for your computer is critical, whether you use Findings or not. We designed Findings so that backup of your lab notebook and accompanying data becomes part of your overall computer backup without any extra work on your end. In other words, if you already use a backup system like Time Machine, CrashPlan, BackBlaze or Arq, you are covered. If you do not have a backup system, I strongly recommend you get an external hard drive and start using Time Machine now (ideally, 2 hard drives, in 2 separate locations). Whatever you use, make sure it is an incremental backup system, so that you not only have a copy of your data, but a history of it.

If you are storing your library on Dropbox, you have yet another backup. Even on the free Dropbox plan, you are able to go back up to 30 days and restore any file up to that time (it can be unlimited with paid plans). One important caveat: there are still situations where it is difficult to restore data with Dropbox, in particular if you delete your entire library, so backing up your computer with just Dropbox is not enough.

That’s it for today! There are many more aspects of data preservation that I would have loved to cover, but this post is already too long and it will have to be for another time. As always, we are eager to improve Findings for your needs. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions, on this topic or any other, let us know via email to feedback@findingsapp.com, to @findingsapp on Twitter or on our Facebook page.