What Is an Experiment?

The word "experiment" has somewhat different meanings for different scientists. Let's reconcile them all, and see how Findings uses the resulting concept.

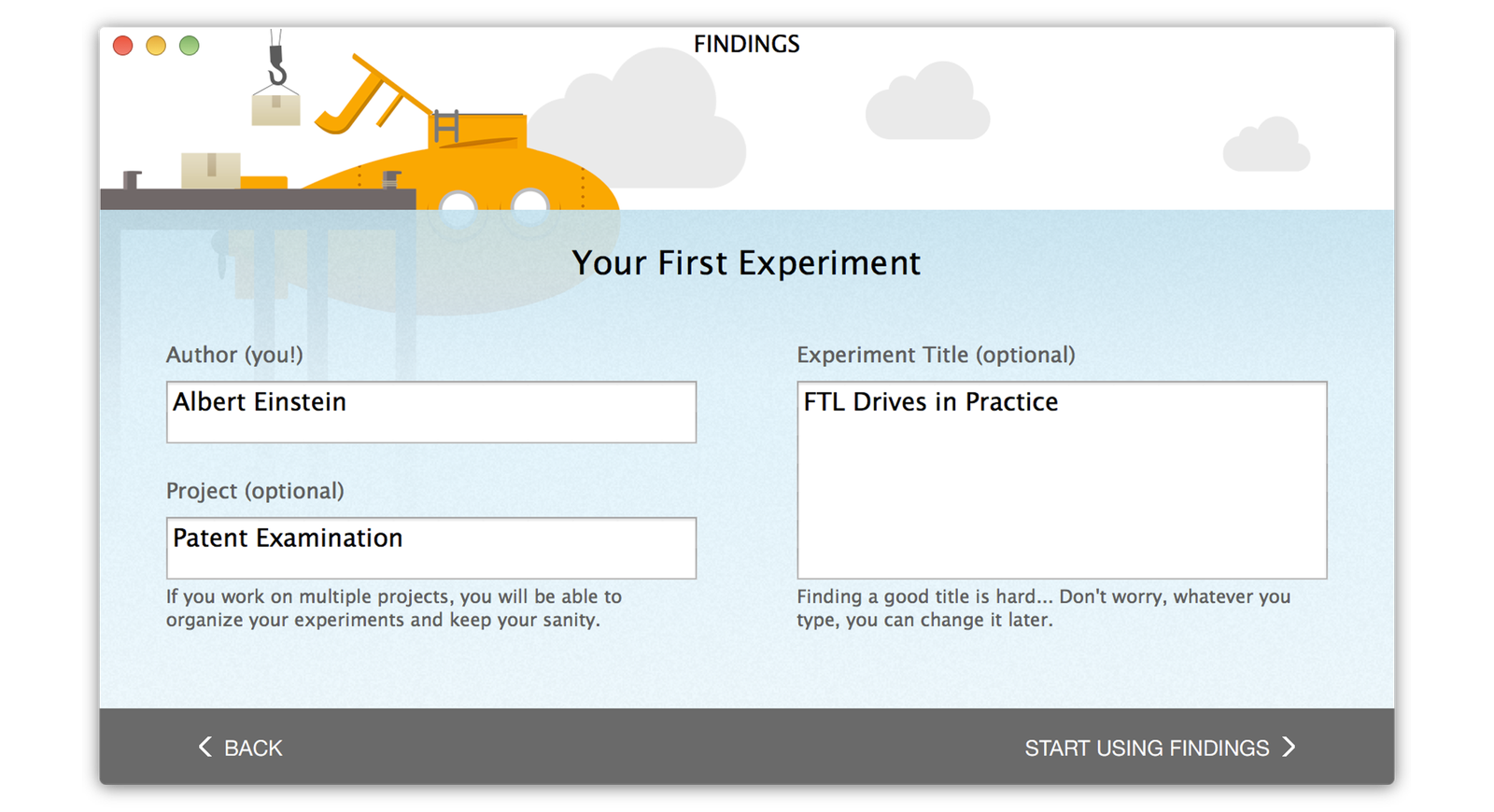

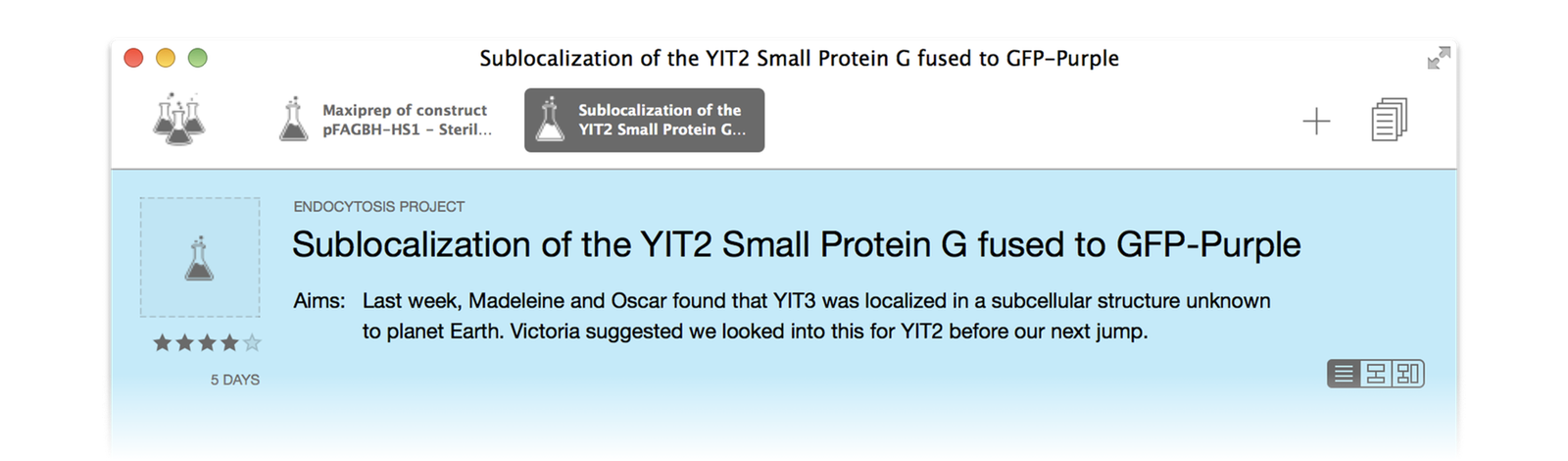

In Findings, experiments are front and center. When you first start the app and go through the welcome guide, your first action is to create a new experiment. The main screen presents all your ongoing experiments. Most of the activity revolves around creating and editing experiments. It begs the question: what is an experiment?

Hypothesis-Driven Experiments

Here is what Wikipedia has to say:

An experiment is an orderly procedure carried out with the goal of verifying, refuting, or establishing the validity of a hypothesis.

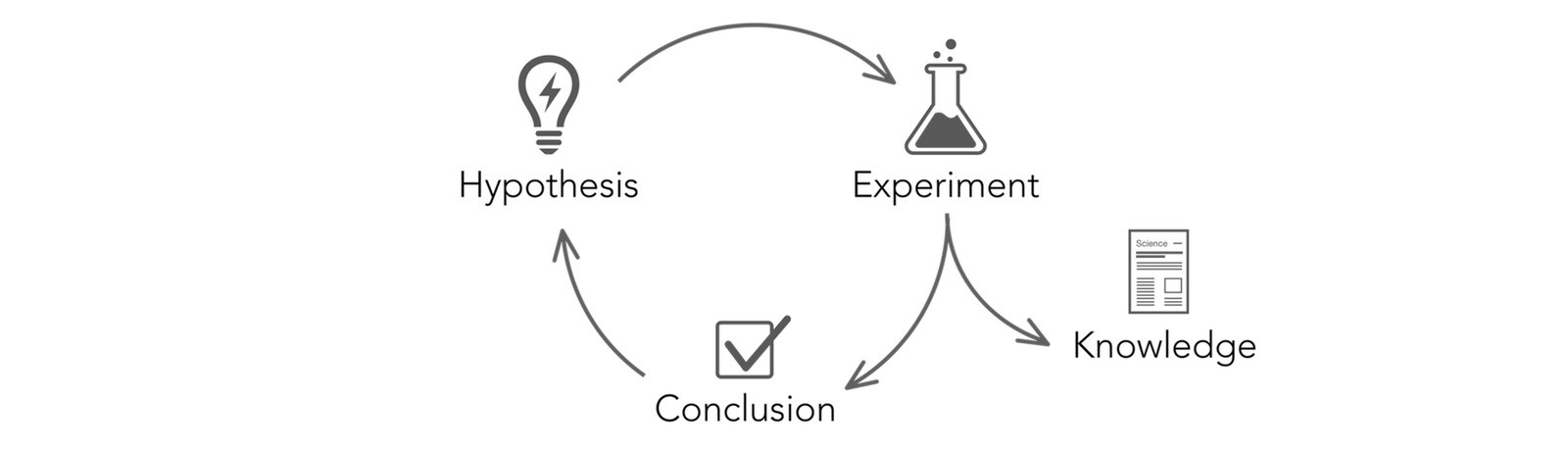

That seems about right, and it is definitely the primary way you can think of experiments in Findings. An hypothesis-driven experiment asks a simple question, which is answered by performing a series of procedures and analyzing their output. The results in turn may lead to a more refined hypothesis, and more experiments. In this ideal scenario, the experimental narrative creates a virtuous cycle, from which knowledge is spit out at each rotation. Eventually, there is enough knowledge for a publication.

This approach is of course fundamental to many fields of research, including biology, chemistry, physics, psychology, social sciences, or even business analysis. It is the way we can understand objects from the real world, like cells, chemicals, atoms, magnets, humans or businesses. Hypothesis-driven experiments are the core components of a research project, and of a lab notebook. But they are not the whole story...

"Experiments" are Not Experiments, But That's OK

The practice of hypothesis-driven science is all nice and good, but in reality, things can get very messy. The path to new knowledge is tortuous, full of twists and turns. Before an exciting story can be written, with a clever hypothesis and a clear conclusion, one has to accept uncertainty and serendipity. To account for how science is done, and still keep track of it in a lab notebook, let's think about the other types of "experiments" that should be considered. Technically, none of what I will describe below is an experiment, hence the quotes in the previous sentence. But we need a word to describe all these things, and in Findings, we have decided that Experiment is the word. Brace yourself, we are about to stretch its definition quite far from where we started.

I am looking at you, cells!

Descriptive and Exploratory Experiments. In biology, it is common to just look at something very closely to try to figure out what it could be or what it could do. For instance, when disabling a gene in mice, the only reasonable thing a researcher can really do is to carefully observe the mice behavior, and survey all its organs, hoping to figure out what's wrong, if anything. Similarly, when pointing a telescope at a portion of the sky, an astronomer hopes to find something unusual and exciting. There is still an underlying hypothesis driving these experiments, but it is typically vague and very broad, something along the line of "This gene is important for process X" or "There must be stuff we don't know about".

Reagent-Producing Experiments. What I call a reagent here is anything material produced by the researcher that can be useful for other future experiments. In biology, it could be a cell line, a mouse strain, a batch of purified protein, etc. In physics, it could be a batch of a new supraconductive material. Of course, even hypothesis-driven experiments produce all kind of intermediary products that you could call reagents. But what I call reagent here is a product that requires a significant amount of work to make, that can be kept around for a while, and that will be repeatedly used in subsequent experiments.

Data-Producing Experiments. We can think of data as a special kind of reagent. Again, hypothesis-driven experiments always produce some kind of data, even if just a few numbers. So what do I mean by data, here? Think large datasets, like microarray data, systematic microscopy images, or crowd-sourced classification of galaxies. This is the kind of data that can't just be looked at easily, but instead requires systematic analysis, preferably computation-based; data that will lead to many more "experiments" to get all the information out of it, including by other members of the lab or other researchers in the future. It's data that keeps giving.

Computational Experiments. Computations are often experimental in nature: based on an hypothesis, the researcher devises a series of computations that exploits existing datasets, and designed to output an answer to the underlying question. In a way, this type is not that different from hypothesis-driven experiments. The methods and workflows are however very different from real-world procedures, and it may not be obvious that computations can fit the idea of an experiment. But they do!

Thanks for your attention

Research Activities. For this last category, I do not dare to actually use the word Experiments. Oops, I just did. By research activity, I mean any of the following: bibliography analysis, lab meeting, workshop, poster preparation, etc. These are clearly not hypothesis-driven (except maybe bibliography analysis), but they are all integral part of a research project, and have probably earned a spot in your lab notebook.

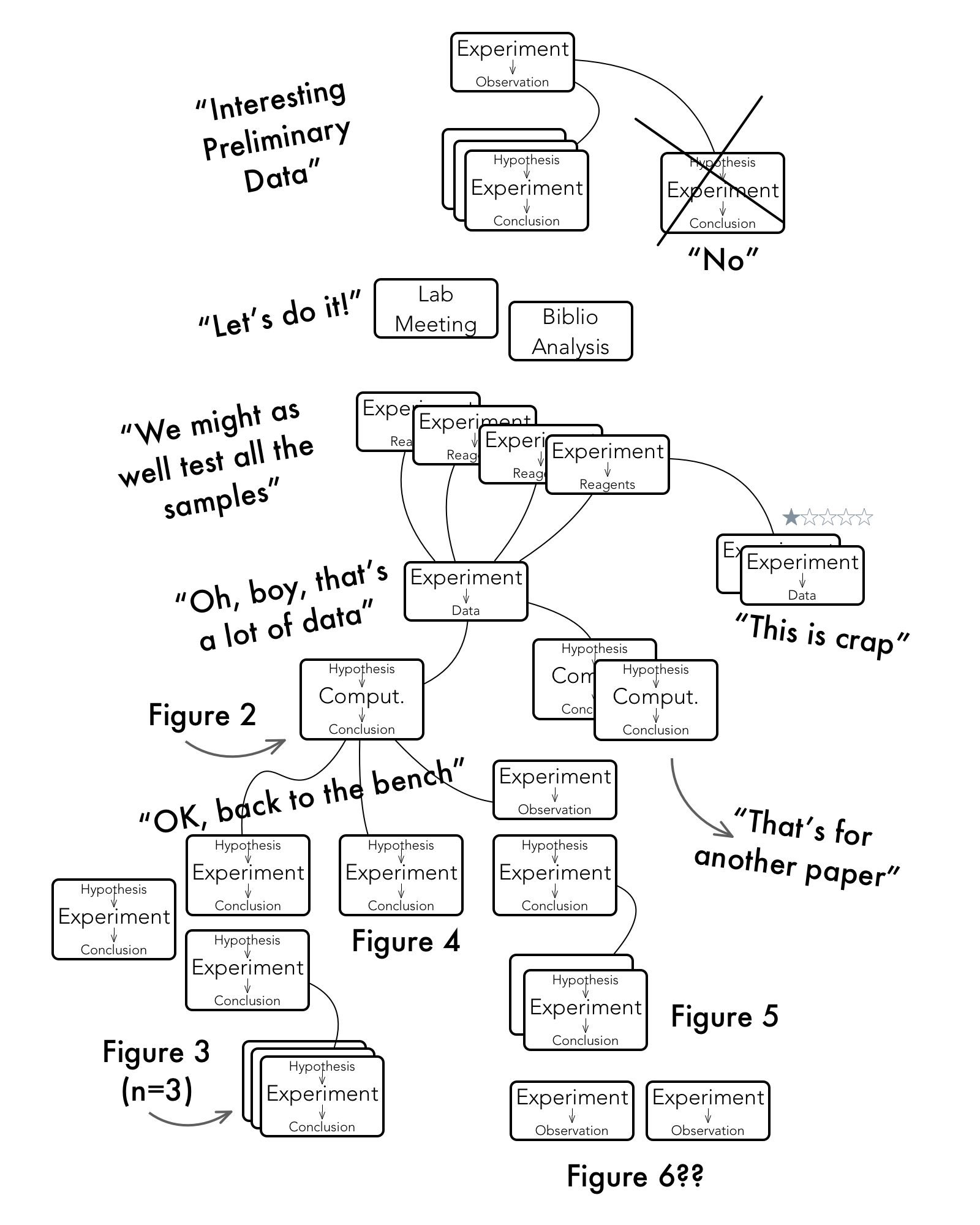

Building a Research Project with Experiments

In the end, all these "experiments" are the building blocks of a research project. There are different types of blocks, and they can be combined and connected in many different ways. All your experiments contribute to the ultimate goal, which is the production of new knowledge. If you think of Experiments this way, maybe a new picture emerges that looks like this...

There are a lot of improvements we plan to make to Findings for project management based on the above ideas, but the foundations are already in place, and you can start building your own structure. What do you think? Let us know via email to feedback@findingsapp.com, to @findingsapp on Twitter or on our Facebook page.